While AI Data Centres Boom, Public Research Hits a Wall

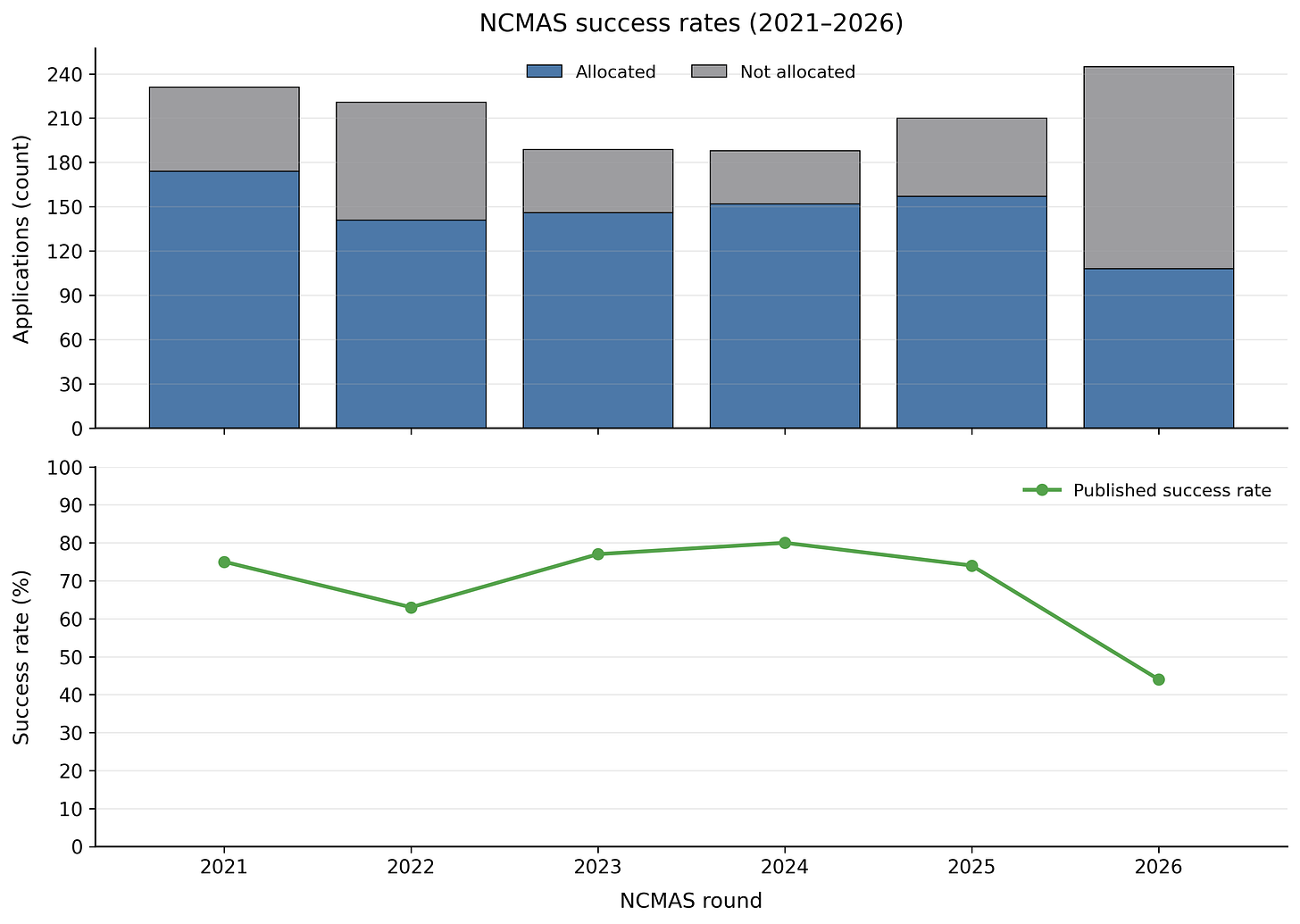

For the last five years, the National Computational Merit Allocation Scheme (NCMAS) has functioned like a steady “electricity grid” for science: a somewhat predictable way to access national supercomputers so researchers and students could run climate models, design new materials, model bushfire risk, study disease, simulate engineering systems, and much more. With its moderate success rate and wide distribution of resources, NCMAS was a rare example of a best-practice funder. Then, in the latest round for the 2026 year, the floor dropped out.

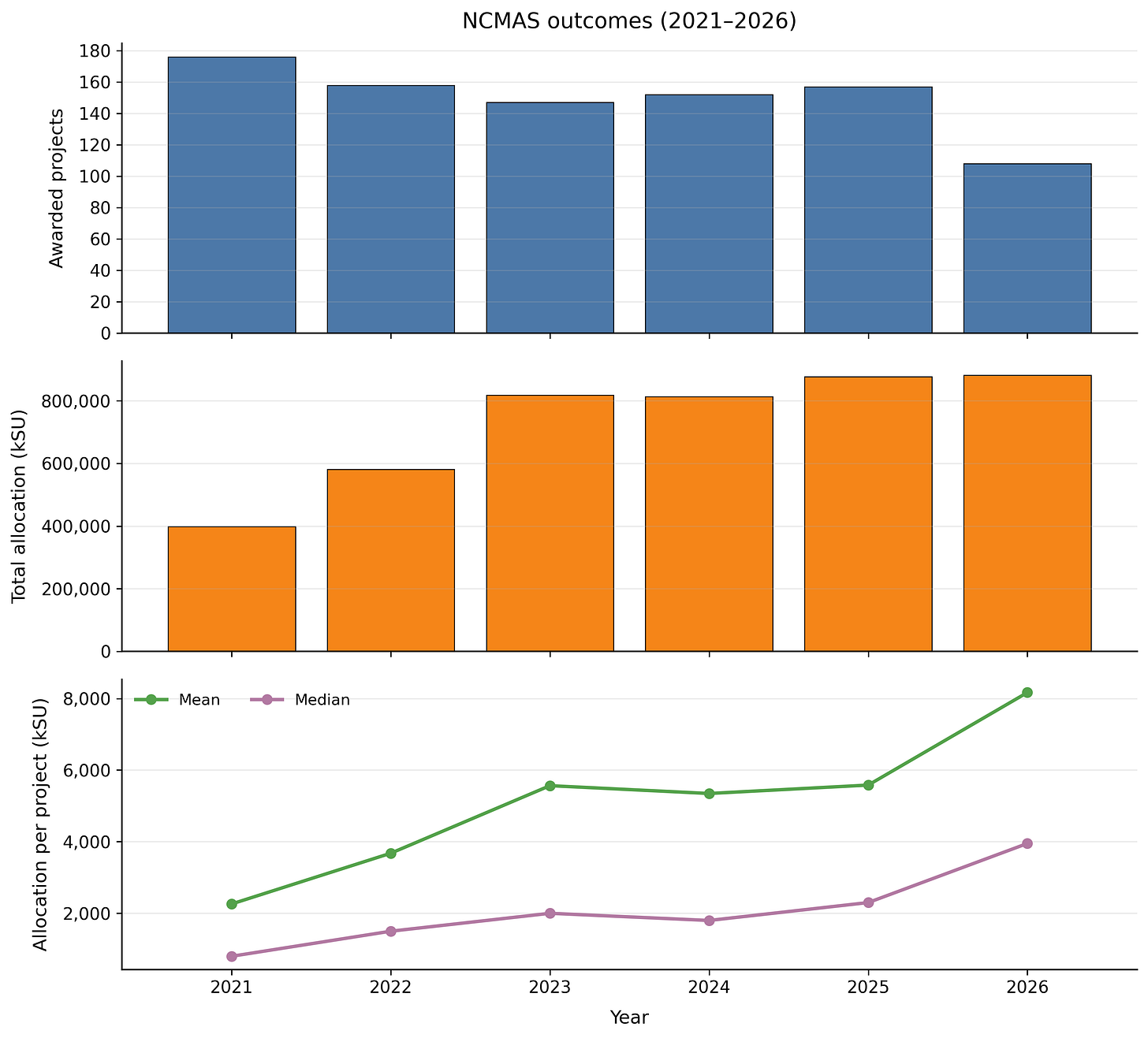

The success-rate fell from the usual ~70-80% range down to roughly the mid-40% range — meaning far fewer groups got access, and those who did tended to receive larger allocations per project. That support is absolutely going to be useful, and drive great work for those research teams that landed support. For the rest - many of whom have relied on this support - practically this is going to lead to broken project timelines, and research teams suddenly unable to do the work government may have already funded them to do, in some cases.

The demand surged far beyond supply, as recently NCI and Pawsey reported 245 applications requesting more than 2.2 billion compute hours, nearly three times what the scheme can provide on the two Tier-1 machines (Gadi and Setonix). Research-sector reporting put it bluntly: oversubscription was so severe that a large fraction of applicants would miss out. A deeper problem that these figures reveal about national risk is that Australia has built a system where large parts of publicly funded research depend on a single, external, merit-based compute allocation round. When that round becomes wildly more competitive, whether through demand shocks, shifting priorities, or simple capacity limits, students and researchers can be left stranded midstream.

And it’s not as if teams can “just pay for it.” Australia’s research funding environment is already tight: ARC Discovery Projects success rates have been hovering around the 15% mark, meaning most proposals fail and even winners run lean budgets. Meanwhile, governments are greasing the wheels for private capital courting data-centre expansion for booming AI workloads; Reuters reported Amazon announcing a multibillion-dollar investment in Australian data-centre infrastructure aimed at expanding capacity for cloud and generative AI. That contrast is hard to miss: rolling out the red carpet for building the compute needed to scale private AI products, while public-interest research teams are forced to ration the cookie crumbs of the very compute power required to deliver outcomes taxpayers already fund.

If Australia wants productivity, sovereign capability, and serious innovation, this is one structural vulnerability to fix. The National Computational Infrastructure (NCI) and the NCMAS program is doing what it can with finite capacity, but the figures show the nation is now relying on a brittle bottleneck, and yet another heavily oversubscribed public research scheme holding up thousands of research and innovation timelines. We need basic continuity to offer stable, scaled national research compute, and transparent reporting of demand vs supply decisions so that the public sector can do the work the public pays for, not lose months or years of progress because one annual allocation round suddenly becomes a cliff.